By Florenda Corpuz

TOKYO – For decades, they lived in silence across the Philippines. Elderly people born of wartime unions between Japanese fathers and Filipino mothers, abandoned by history, and invisible to policy. Now, for the first time, Japan is extending a hand to bring some of them home.

Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba will meet a group of people of Japanese descent, known as Nikkei-jin, during his official trip to the Philippines from April 29 to 30. The encounter is more than ceremonial. It marks the beginning of a long overdue gesture: Japan will invite a select group of stateless descendants to visit this summer in what advocates call a symbolic return.

“It is fully reasonable” for the children of Japanese nationals who migrated to the Philippines “to visit Japan and search for their families,” even if it is funded by Japanese citizens. He made the remark during a Budget Committee session in the Diet last month, according to Jiji Press.

“This is the first time the Japanese government is inviting them in this way,” Norihiro Inomata told Filipino-Japanese Journal. He is the representative director of the Philippine Nikkei-jin Legal Support Center, a Tokyo-based nonprofit that has long worked on behalf of the community. “We call it homecoming.”

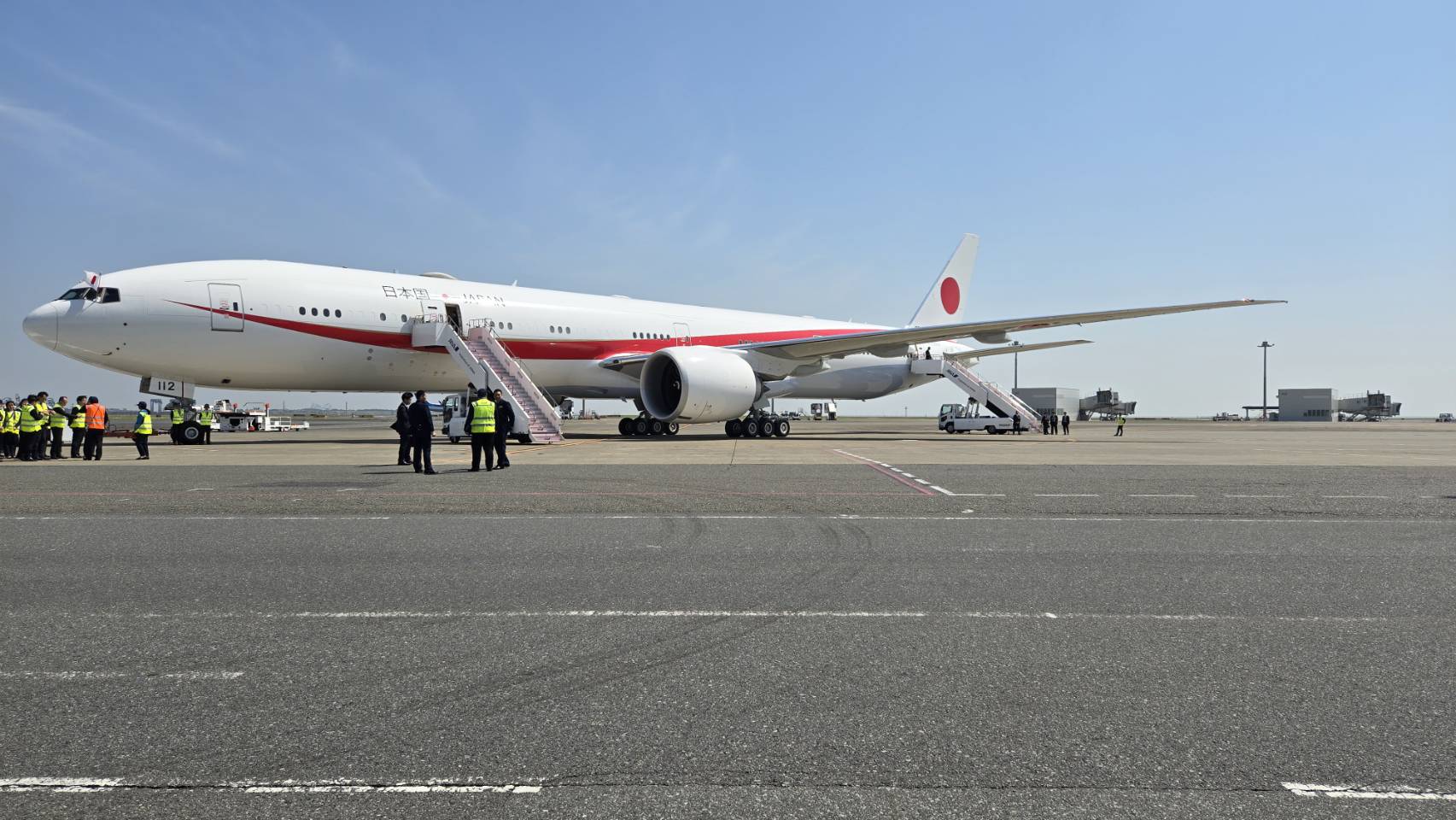

Japanese Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba heads toward a government aircraft at Tokyo’s Haneda Airport on April 27, 2025, as he departs for a four-day official visit to Vietnam and the Philippines. (Photo courtesy of Shigeru Ishiba/X)

Scattered throughout the country, especially in Mindanao, these men and women, now between 79 and 97 years old, are the children of Japanese soldiers and settlers who arrived before and during World War II. When the war ended, many of their fathers were killed or repatriated to Japan. The children, often left with Filipino mothers, grew up hiding their identity to escape postwar discrimination.

“They survived by staying silent,” Inomata said. “But their desire to know their roots never faded.”

According to the center’s data, 3,815 Philippine Nikkei-jin have been documented. Of those, 1,649 obtained Japanese citizenship, 1,841 died stateless, and 134 are still alive. Only 49 still hope to reclaim their Japanese citizenship. Many others have passed the point of hope or turned to other countries for legal recognition.

Inomata said the Japanese government will invite 10 individuals, a separate group from those Ishiba will meet in Manila. These individuals are believed to be of Japanese descent but lack documentation. Their cases are fraught with wartime loss and a decades-long absence of official recognition.

“This is urgent,” Inomata said. “If they pass away without recognition, their descendants lose everything, their connection to Japan, their identity, their right to belong.”

Ishiba’s meeting with President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. will focus on economic, political, and security ties under the two countries’ strengthened strategic partnership. But for the descendants watching quietly from the sidelines, the visit holds deeply personal meaning.

“All Philippine Nikkei-jin share one wound. They were separated from their fathers,” Inomata said. “What they want is not money. They want to know where in Japan they came from.”

So far, 718 have found their father’s place of origin. Others continue to search. With the center’s help, 323 have obtained Japanese citizenship.

“The impact of finding that origin is profound,” Inomata said. “It means their children might one day live and work in Japan. It gives them something to pass on.”

Many survivors have grown old in silence, living without papers, overlooked, and nearly forgotten. But their stories are beginning to be heard.

“They are not asking for compensation,” Inomata said. “They just want to be seen.”

As Japan prepares to welcome them, it also begins to reckon with a quiet legacy of its wartime past, one not etched in the halls of government but in the mountains of Luzon, the Visayas, and Mindanao, in the memories of families who waited for a return that never came.

Now, at last, the invitation has arrived.