By Florenda Corpuz

A Glimpse Inside Fuchu Prison

Fuchu Prison, the largest all-male penitentiary in Japan, houses the country’s highest number of foreign inmates, including several Filipinos. Once lured to the Land of the Rising Sun by dreams of a better life, these individuals now face the stark realities of incarceration, while grappling with a complex Japanese penal system, cultural isolation, and rigid routines.

Located in a quiet neighborhood of western Tokyo, the sprawling facility accommodates roughly 1,700 prisoners, around 300 of whom are foreigners. Among them are six Filipinos: two in their 60s serving life sentences and four in their 30s. The language barrier poses a considerable obstacle for these inmates.

The interior of a group cell at Fuchu Prison | Courtesy of Anthony Trotter

“Almost all foreign inmates cannot speak Japanese,” says Hiroyuki Yashiro, the prison’s chief, highlighting the isolation many experience.

Life inside Fuchu Prison follows a meticulously regimented schedule. Each day begins at 6:45 a.m. with roll call, followed by three scheduled meals and eight hours of mandatory labor in between. Prisoners engage in tasks such as woodworking, sewing, and automobile maintenance. Those who refuse to work face disciplinary action.

In exchange for their labor, inmates earn a modest monthly work money of around 4,000 yen (approximately 1,500 pesos), which they can use to purchase basic necessities.

Single cell

Prison conditions vary based on age and health. While inmates over 70 work in air-conditioned spaces, most experience hot summers with limited cooling, such as fans. To manage the heat, inmates use salt tablets and frozen candies, as budget constraints limit the availability of air conditioning. In winter, the cold presents its own challenges.

Hygiene routines are strictly regulated. Prisoners are allowed a 15-minute communal bath three times a week. Foreign inmates also have limited access to English-language radio and newspapers, providing a brief connection to the outside world.

The communal bathhouse used by inmates

Medical care is a pressing need within the prison, as about 70% of inmates, many of them elderly, require treatment for physical or mental health issues. Fuchu is equipped with medical facilities staffed by on-call nurses and doctors available 24/7.

“Our rules may seem strict, but in Japanese prisons, lives are secure. The rules here are for the inmates’ safety,” Yashiro emphasizes.

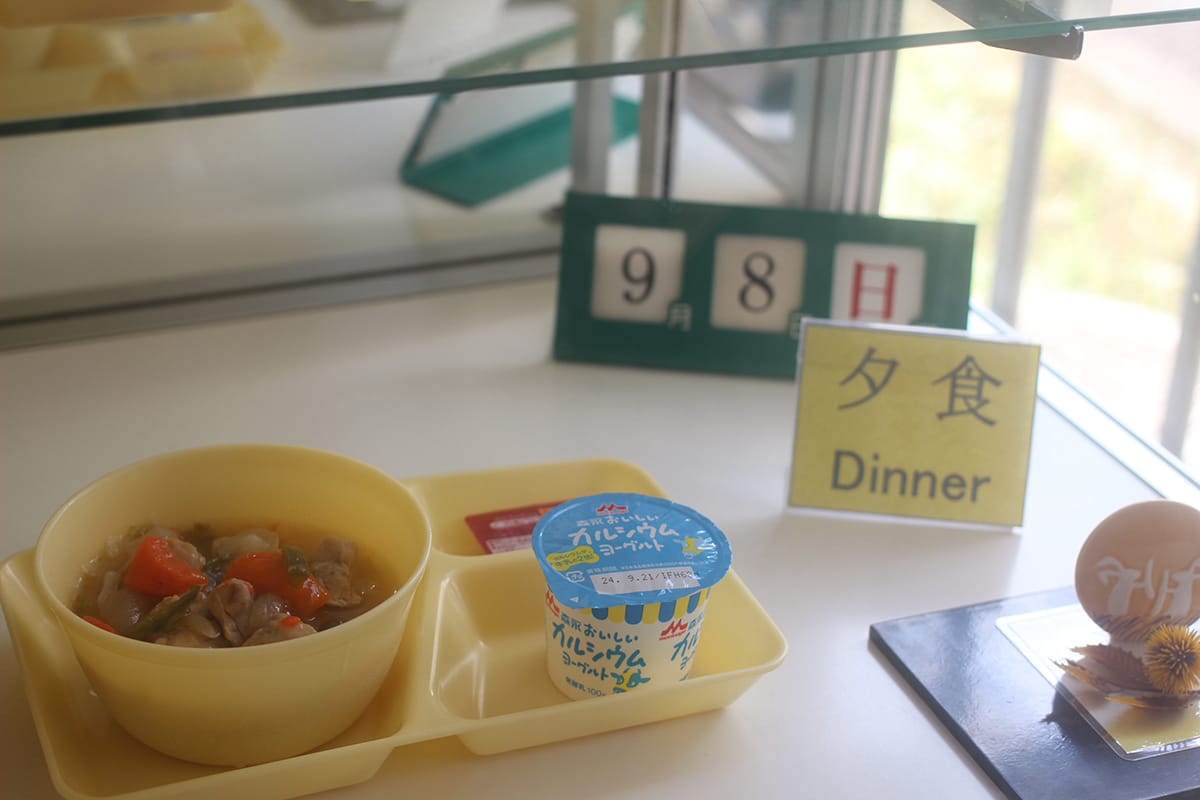

A sample meal served to prisoners

To prepare inmates for life after incarceration, Fuchu Prison offers job training programs. However, reintegration remains a significant challenge. Yashiro acknowledges that many struggle to secure employment or housing, often leading to recidivism. In Japan, approximately 40% of released prisoners face these issues, which frequently result in their re-entry into the system.

The Filipino Experience

For Filipino inmates, cultural differences and the lack of family support heighten the challenges of incarceration. A former Filipino inmate, who served time at Chiba Prison, shares his experience in a letter to the Filipino-Japanese Journal.

“The lifestyle there in prison is not like ours, where there’s plenty of time to read books and magazines. There was very little free time,” he writes, expressing regret for his actions and reflecting on the lessons he learns during his sentence.

He also raises concerns about alleged mistreatment, stating, “I always inform our embassy about how I am being treated.”

A cell for foreign inmates, marked “F”

He has since returned to the Philippines.

The Philippine Embassy tells the Filipino-Japanese Journal that there are no documented cases of abuse, violence, or ill-treatment of Filipino prisoners. However, they address isolated allegations, including the letter sender’s complaint and a report from another Filipino inmate claiming to have been physically attacked by a fellow prisoner.

Role of the Philippine Embassy

The Philippine Embassy currently oversees the welfare of 53 Filipino prisoners and detainees in Japan who consented to report their incarceration to the Philippine Embassy in Tokyo (25), and the Philippine Consulates in Nagoya (13) and Osaka (15). Its responsibilities include verifying case details, conducting jail visits, and ensuring access to basic necessities and medical care. The Embassy also collaborates with Philippine government agencies to support reintegration efforts.

“The greatest number of crimes involving Filipino nationals are ‘victimless’ crimes, such as overstaying and false declarations, as such acts are considered criminal offenses and tried in criminal court,” the Embassy shares with the Filipino-Japanese Journal.

Exterior view of Fuchu Prison, featuring its light brown facade

However, the Embassy acknowledges that their assistance and support for Filipino inmates are limited by Japanese laws. They say, for instance, that an inmate’s letter written in a mix of Tagalog and English was returned with instructions to use only one language, as all mail is censored.

According to the Embassy, deportation of Filipino prisoners who have completed their sentence remains a sensitive issue, often carried out discreetly and without prior notice to the inmate or their family. They also note that they cannot legally track the whereabouts of individuals permitted to remain in Japan during reintegration into society, due to the strict enforcement of privacy laws, unless the individual or their family reports this information to them.

“If a Filipino national violates Japanese law, they are subject to Japan’s judicial system,” the Embassy tells the Filipino-Japanese Journal. “While the Philippine government cannot shield them from the consequences, we ensure their rights are respected and that they are not discriminated against.”